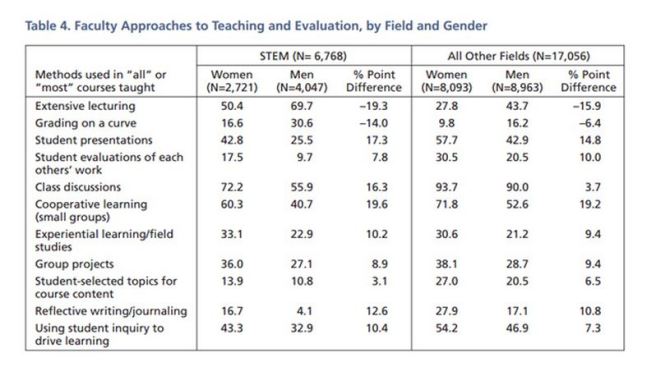

I’m kind of shocked by the following study about the teaching methods breakdown between men and women:

I don’t know how to interpret this, people. Either men don’t know how to teach or they don’t know how to answer such surveys. But seriously, it can’t be that men collectively are so much worse at teaching than women. Then what is happening? How come that the only areas in teaching where men outnumber women are the most detrimental practices of all, curve grading and teacher-centered lecturing?

I am in a STEM field, and I can believe that this happens. But you know what the shocking fact is? In STEM fields, these excellent women teachers also consistently get lower student evaluations than men. The reason is that students simply cannot believe that these women are experts in their fields and competent enough to teach them. The first time I taught I got student evaluations of the form “she is a good teacher, but not an expert in her field”. It turns out its not just me, all my women colleagues also get such reviews, and the way to avoid them is to keep boasting about your accomplishments in class! “When I worked on such and such problem, I found …” and so on.

LikeLike

Prejudices take a long time to die out, unfortunately. But that’s one of the main reasons students come to college: to get rid of stupid prejudices they are bringing from home.

LikeLike

I hope you are right. In this particular case of women and STEM though, I am not sure how optimistic one should be. There are _very_ few women STEM professors, and many students can virtually go through college without taking more than one or two classes from women professors; as a result, it is not uncommon to come across graduate students and even faculty who haven’t yet gotten rid of these prejudices. A lot of STEM-based companies are also notoriously woman-unfriendly, so the industry isn’t much better either.

LikeLike

Only a short time ago there were no women professors, period. The academia has transformed in an incredible and phenomenal way in just a few decades. STEM is the very last bastion but it will fall very very soon. 🙂

LikeLike

@Luna –

Yep. I can only think of two women professors I had in my STEM classes (three, if you count the professor in charge of the microbiology labs, but I never interacted directly with her), and while they were both wonderful, I find I still default to thinking “he” when someone talks about a (gender-unspecified) professor! And I was the sort of kid who, if you asked me to draw a scientist, would’ve drawn a woman because I wanted to be a scientist.

LikeLike

I am finding that gender has a huge impact on the Humanities class I’m teaching. My mentor for this class is a man who loves the lecture component of the course and hates the discussion portion. He feels that running discussion groups is beneath him. I am not excited about the discussion groups either, but not because I think they are beneath me. They are led entirely by students, and they typically do mediocre work. That’s frustrating. But interacting with students makes teaching worthwhile to me. The lectures are simple ego trips — I am brilliant, listen to my brilliance!! — but the student interactions have the potential to be decent.

LikeLike

Here is a quote from the study about this teacher-centered learning and why it is not the best: “Use of extensive lecturing in class has been shown to negatively affect student outcomes, such as engagement and achievement (Astin, 1993). In addition to using this less student-centered approach, faculty in STEM are also more likely than their counterparts in all other fields to grade on a curve, which disguises the actual changes in learning and acquisition of skills of individual students.”

Since I do foreign language and literature, at least 50% of each class session is group work in my courses. Of course, I direct the students and manage the groups. Without these group activities, my students wouldn’t be able to say anything in Spanish. Let alone analyze texts or write.

LikeLike

I’m not sure STEM classes can always do student-based learning. I know I can’t learn that way, and I know people who complain when a physics professor teaches that way. You really learn the most from the homework, when you’ve been taught the basic concepts in lecture and now have to learn how to apply them. A lot of the time, if you haven’t had the chance to struggle with that application, it’s harder to remember.

On the other hand, it’s much easier for a language class to be participation-oriented because most of the actual exposure to language and analysis other than your own comes from the class itself. In a science or math class, we can’t do the critical thinking or analysis in class because we don’t have the concepts and we don’t have the time to cover everything. Even in a participation-based math class, we still get most of our exposure from the homework.

LikeLike

“You really learn the most from the homework, when you’ve been taught the basic concepts in lecture and now have to learn how to apply them. A lot of the time, if you haven’t had the chance to struggle with that application, it’s harder to remember.”

– So why not explain the concepts in class and then get people to work together on applying them? This would be a good intermediate step between explaining the material and leaving the students to struggle with the application on their own.

“On the other hand, it’s much easier for a language class to be participation-oriented because most of the actual exposure to language and analysis other than your own comes from the class itself.”

– Easier or not, it is only very recently that student-oriented learning started being used in foreign language learning. The most recent Beginners Spanish class I observed was taught by an older colleague who stood in front of the class for 50 minutes and recited a lecture on the use of Spanish verbs. The resistance to participation-based learning is still very strong in my field. And you know why? Because nothing is easier than reciting a lecture. I’m ashamed to confess that I sometimes do it too when I feel lazy. 🙂

LikeLike

” So why not explain the concepts in class and then get people to work together on applying them?”

-A lot of times, people will work on the homework in pairs or in small groups. It’s encouraged. It doesn’t work all the time, though, especially in lower-level classes where the students’ abilities can range from no exposure in high school to proficient at the college level. I get fed up in my chemistry class because the group activities don’t do anything for me; they’re geared toward the freshman biology majors who haven’t necessarily been exposed to the material and who haven’t always taken college classes. When we do those activities, I find them relying on me for all the right answers. Nobody learns in that situation. There are also students who don’t learn best by working with other people, who do their best work on their own and are only willing to work with others on the homework when they’re really struggling. I’ve never come across this in other classes–just math and science.

LikeLike

I’m like Pen in that I have trouble seeing STEM classes always being able to do the same kind of student-driven learning that you can have in the humanities — at least, not without hiring A LOT more professors to teach introductory physics, chemistry, organic chemistry etc. My classes in those subjects had hundreds of students in them, and while the lab sections were definitely in line with the good teaching practices you list above — small groups of students worked on their own to do whatever the lab objective was — I can’t see classes of 300 people realistically doing anything other than just listening to the professor lecture. (These classes also usually had discussion sections, which were much smaller, met once a week and revolved around student questions).

However, I have had at least one STEM class that was entirely conducted in a student-centered way: we all split up into groups, taught ourselves part of the subject matter, and then presented what we had learned to the rest of the class. This was a summer class with, like, fifteen people though. And it was cell biology, not chemistry or physics.

But anyway, I guess my point is that, while my experience of having the STEM subjects taught is almost exclusively lecture-driven, I can see it working at the small-group level, but the classes would have to be made A LOT smaller.

And I was taught physics in high school in exactly the way that you suggest, and that Pen says does not work: the teacher would lecture for a VERY SHORT time on whatever general principle we were learning that day, and on how to set up, and solve, problems using that principle, and then he’d turn us loose to work on problem sets for the rest of the hour and a half class period. I thought it worked well enough, and I learned some stuff pretty well, but when I took physics again in college there was material covered that I hadn’t been exposed to.

LikeLike

” I can see it working at the small-group level, but the classes would have to be made A LOT smaller.”

– This is precisely why in the Humanities we fight very hard to avoid these 300-people monstrosities foisted upon us. Sitting in a huge room with 300 people and listening to a prof mumble something monotonously for an hours is NOT education. It’s a rip-off.

LikeLike

You said something about how we fight hard in the Humanities to keep class sizes small, but the Humanities program I’m working in does just the opposite, saying that students need the experience of being 1 out of 100 in a lecture hall. I hate it, and I want out. It’s bad pedagogy, and it makes everyone (except the director) miserable.

LikeLike

“I’m working in does just the opposite, saying that students need the experience of being 1 out of 100 in a lecture hall”

– This is absolutely ridiculous. I agree that this is extremely bad pedagogy and will not teach anybody anything.

LikeLike

Based on what I’ve read in the comments section of the Chronicle of Higher Education, these are the reasons I would give for the STEM fields being the worst.

* More than in other fields, in the STEM fields, the rewards come from bringing in grants and publishing. It reduces the level of effort that faculty put into teaching well.

* The belief that reducing lecture time will dilute the course content and rigor is more common in STEM than in other fields.**

* There’s a macho hazing that goes on in STEM fields. If a student can’t succeed in straight lecture teaching, it means the student isn’t cut out for STEM fields.

** I have no idea how they reconcile grading on a curve with their claims of rigor.

LikeLike

“There’s a macho hazing that goes on in STEM fields.”

– I don’t want to offend anybody but macho is the last word I’d use to describe the usually very nerdy, quiet and sensitive men in STEM fields. Thees are qualities I like, so I’m not being critical of anybody.

LikeLike

My father used to joke that a boy does not become a man until he can perform multi-variable calculus.

LikeLike

Maybe “macho” is the wrong word, but I see where Anonymous is coming from. There’s a pride taken in the difficulty of the subject matter, and sometimes having a student-unfriendly class structure just adds to the mystique. We are tough, we are smart, we survived Engineering Physics/Organic Chemistry/Calculus II/whatever.

LikeLike

“There’s a pride taken in the difficulty of the subject matter, and sometimes having a student-unfriendly class structure just adds to the mystique. We are tough, we are smart, we survived Engineering Physics/Organic Chemistry/Calculus II/whatever.”

– Now I’m wondering what possessed the previous commenter to refer to this as “macho.” But it sounds really great that students actually like difficult courses. I wish mine were more like that.

LikeLike

@thevenerablecorvex – Ha! Your father sounds like my father.

LikeLike

Loud or quiet, nerdy or not, sensitive or not there are many different ideas of what it takes for one to be considered macho aka “a real man”.

I think in the context that Anonymous is saying macho the ability to succeed in straight lecturing is seen as a test of masculinity or manhood.

From a bunch of intellectual guys trying to prove who is the smartest from a bunch of athletes trying to prove who can do the most push ups to a bunch of car guys trying to prove who can change a car’s oil the fastest…..

Point being different groups of guys have different measurements of macho (oddly, each of those groups would probably look at the others and think they were unmaly for not doing what they are doing).

The existence of The Macho is pretty messed up but I think it’s a fitting use of the word here.

LikeLike

Only recently we discussed on this blog that explaining the meaning of Spanish words to a Hispanist is condescending and rude.

LikeLike

“More than in other fields, in the STEM fields, the rewards come from bringing in grants and publishing. It reduces the level of effort that faculty put into teaching well.”

-This depends on the school. There are schools whose faculty don’t care about their undergrads. There are also schools whose faculty do care and are more than willing to teach their students well.

“The belief that reducing lecture time will dilute the course content and rigor is more common in STEM than in other fields.”

-That’s not what I see as a student in a STEM field. With less lecture time, it’s more difficult to learn the material. The content isn’t diluted; instead the students have a harder time trying to learn even basic concepts.

LikeLike

““The belief that reducing lecture time will dilute the course content and rigor is more common in STEM than in other fields.”

– The fear of relinquishing control is the bane of all not-so-good teachers.

LikeLike

To answer your question, Clarissa, I think it’s an age thing. Page 47 of that document breaks down the teaching methods by faculty status (full, associate, etc.), and you’ll find that best practices are also dominated by younger faculty. To me, this implies that senior faculty are just stuck in their ways and are slow to change. Since the most senior professors tend to be men (especially in STEM fields) for reasons I am sure I don’t have to explain here, this results in a larger fraction of men teaching via traditional lectures. Unfortunately this study doesn’t seem to break down the results by both gender and seniority…

LikeLike

Ah! OK, this makes total sense. I knew this couldn’t have been a gender thing because that simply makes no sense. But the generational explanation really works.

Thank you for helping me figure this out! This is the best thing about blogging. 🙂

LikeLike

I wonder if women in STEM fields are more likely to try and use innovative teaching skills because there is more pressure on them to match up to male instructors? Even as a graduate student instructor, I felt like the students always assumed the male grad students were more competent (of course this was in a very male dominated field, some of the course sections had no women).

Oh, and macho exists in the STEM world. There are some amazing professors that put forth a lot of time into teaching, but there are still many arrogant macho men. Believe me, you even get muscle head engineering profs that hit on the female students. It’s nasty.

LikeLike

Perhaps there’s some kind of confounding effect going on here? The gender balance tends to be more males in STEM and more females in not-STEM subjects, so we need to know if the difference is due to disciplinary culture or gender of teacher or both?

I’m based in the UK so may not be experiencing the same things as the US/North American system, but it seems to me that STEM classes especially at lower levels are often taught as large lecture plus lab (often also in large class sizes, but with students working in smaller groups overseen by a TA or equivalent), whereas humanities/social science classes are more likely to be taught in smaller sections or as lecture plus small group seminar. In my department, and other places I’ve taught, we are strongly pressured to keep practical classes as full as possible to avoid needing too many repeat sessions to accomodate all the students (because booking labs is a challenge and because otherwise STEM staff would end up with lots of extra teaching hours from all those repeats, either costing money or costing time spent on other duties) and to not do any kind of seminar based smaller-group teaching until the final year.

I can’t help noticing that labs, at the heart of much STEM teaching, are lumped in under ‘experiential learning’, and are apparently only used by a quarter to a third of STEM staff – that seems extremely odd! Especially if that category also includes ‘problem sections’ and fieldtrips. Maybe ACADEMICS in your systems don’t teach these labour-intensive classes, and they’re written by profs and actually delivered by TAs/contingents/teaching onlys (as was the case at my own InternationallyReknownedUniversity alma mater), or written and taught by non-profs?

Or is this where ‘bad at replying to surveys’ comes in? In my department the female faculty are just better at learning and reusing the edu-jargon than the males, overall… and ‘experiential learning’ is the most edu-jargon-y term on the list, especially conflated with field studies like that.

Personally, I find most of the social/student centred modes of learning frustrating and not helpful in helping me learn academic content, and always have done – maybe because I’m socially inept, but I find that construction of proper understanding happens in lectures, as a result of lectures allowing me to have ‘aha’ moments or ‘wtf?’ moments and follow them up alone by reading or by questions, or by reading the reading list materials. I can’t be the only one, and it’s worth noting that ideas about what teaching methods are best are those that suit the majority of the studied students…

Small, self-selected group discussions or practical exercises are also useful, but most full class exercises drive me nuts. This is probably why my weakest area of academic achievement has always been languages, where as you are always reminding us class interactions and speaking in class are absolutely central to good learning!

LikeLike

Of course, you can’t learn to speak a language without speaking it. 🙂 Even somebody as unsociable as I am has to recognize it.

In general, a concept one learns through passive learning has to be applied in practice at least 6 times to become part of one’s active knowledge. In languages, this becomes even worse. A word has to be used between 10 and 15 times in an active context to become a permanent part of one’s vocabulary.

LikeLike

Hence, I’ve only really enjoyed studying dead languages or learning bits of languages by being in places where the language is spoken, needing to use words and learning to understand by listening and watching, rather than by taking classes 🙂 And despite years and years of foreign language studies at school and university level, I can barely read children’s comic books in 2 or 3 European languages, menus and basic instruction signs in a few, muddle through (with a dictionary) reading poetry and prose in a couple of ancient ones, and just about order a drink or apologise for being English in maybe 4 despite having travelled, working in a very international group of people etc. I am in AWE of people who can learn multiple languages and have proper conversations in them.

But like Pen, I find that learning in STEM does progress best via independent study, especially for students likely to specialise in these topics. Small group work tends to mean that many weaker/lazier/more scared of the material students will rely on whoever in the group is ‘better’, and not learn because they don’t try (unlike languages where one person must reply to the other, so at least TRY to take part in a conversation), and students who get some ideas quickly feel that they are wasting their time or being held back by the others… Maybe STEM students are more likely to be unsociable and not so keen on social learning situations, too?

Pure lecture is the perfect method, because we can’t customise classes to the needs of only a few students, but equally I think some lecture is important because we should cater for the needs of all groups of students. In my experience – and I am generally seen by colleagues and students as a good teacher (though of course that may be compared to other VERY bad STEM teachers!) – I find that lecture-short activity-lecture classes with reading or independent learning activities like problem sheets as supplements, coupled with practical sessions, works well. I am also not a believer in MAKING people join groups if the purpose of the class is to learn technical material – for some people, it will just make things much harder. If one of the aims of the class is to work together to solve a problem, then you MUST be in groups, but if not, I like to use what little professional lee-way I have to allow students to learn in the way that best suits them.

LikeLike

@JaneB – my introductory chemistry lab TA had a nifty way to get around the problem you mention of not everyone pulling their weight equally in small groups: he gave us all an aptitude test at the beginning of the semester, and grouped like scorers with like. I was sorted into one of the higher-scoring groups, and we did all seem to be on the same page as far as knowing what we were doing and being able to contribute equally.

(I am unsure how well this worked for the lower-scoring groups, but I seem to remember everyone being able to complete the labs. Maybe they just needed more help from the TA.)

So that was a good small-group experience, but I had a bad one in Physics II. No one wanted me in their group*, but that was A-OK because I knew what I was doing and could figure out the lab on my own, but sometimes the TA would insist that I pair up with *SOMEONE*, or I would occasionally get stuck. Luckily there was another TA observing the class, so I’d ask her to be my partner.

*Their loss! Physics II is electromagnetics at my alma mater, and my dad is an electrical engineer who spent most of my childhood explaining higher-level math and electromagnetics concepts to me and my siblings. But my speech is halting, so few people can see my intelligence or knowledge when they meet me.

LikeLike

So, I teach in a physics department. I do a lot of lecturing, but I also give them group work at times, I break up the lecture with questions to discuss, I give them a lot of activity-based homework (e.g. do a computer simulation). I often begin class by discussing something from an assignment that was given to get them ready for the day’s lecture, and rather than just launching into my lecture I take questions and work off their questions as well as their responses to my questions. I mix it up. I would point to a few phenomena:

1) While lecturing exclusively is sub-optimal, it has become trendy in certain circles to denounce lecturing to the point where if you do it at all you feel like you have to apologize. (This is only true in certain circles.) The more progressive types have managed to become very rigid in their own way.

2) STEM subjects tend to be more sequential than some fields. Prereq chains are longer. And official course descriptions were written by people who wanted umpteen million things covered in each course. Most interactive methods require stopping and taking time…which is great for the students, but also means that you must spend less time on something else This is fine if you have the flexibility to say “You know, we can’t cover everything so we won’t.” But if the person teaching physics 102 is breathing down your neck to cover everything in the official description of physics 101, well, the simplest way to rush through that is to lecture.

I do everything that I can to advocate for putting fewer topics in 101, but this is an uphill battle. And often the people who want those topics in 101 aren’t even other physicists teaching 102. They’re engineers who want us to cram into a year what other schools might cover in a year and a half.

3) There’s lecturing and then there’s lecturing. Even when I’m not using clickers, or group activities, or whatever, I’m taking a lot of questions from the students, and I spend as much time working off of those as I do presenting what was in my notes. I’ll often say “OK, somebody tell me what I should do in step 2 of this calculation?” and then deliberately call on the students who aren’t likely to have the right answer (if they raise their hands, nobody is forced), so I can identify and (gently) correct the misconceptions. If you visited one of my “lectures” you might think it’s a pretty discussion-oriented class. But because I don’t always use sort of product (worksheet, technology, whatever) tested and marketed as “interactive”, the hip, young, progressive types would sneer at me as being old-fashioned, while the senior faculty think it’s great that the students are interacting with me so much.

LikeLike

As to curves, it’s harder than you might think to judge the difficulty of a physics problem in advance. If I write a test where people all miss a problem that I thought would be easy, and the process that they follow is incorrect but at least shows some understanding of how to approach it, it’s tempting to say that maybe I should go below my target percentage.

I mean, is 70% good or bad? It depends on how hard the questions are, right? 70% on an easy test might be unremarkable, while 70% on a hard test might mean you’re amazing. If I start off with, say, the goal that 70% (or whatever) is the cutoff for a C, and then I see people take incorrect but intelligent approaches, and the class average is below 70%, maybe I need to recalibrate.

So what I usually put in my syllabus is some grading scale with fixed percentages for grades, and then say that I reserve the right to be more lenient if merited.

LikeLike

” If I start off with, say, the goal that 70% (or whatever) is the cutoff for a C”

– How come you get to decide this on your own? Doesn’t your institution decide what percentage corresponds to which letter grade? This is their first time I hear of anything of this kind.

“the class average is below 70%, maybe I need to recalibrate”

– Why? It never occurred to me to measure the class average. It sounds a little like calculating the average temperature of patients in a hospital? 🙂

LikeLike

My institution doesn’t have a percentage requirement for a letter grade. I can write a super-hard test where you need to be a genius to get 50%, or I can write an easy one where any idiot could get 80%. Or anything in between. I’m supposed to write what sort of test I want, recognize what type I wrote (easier said than done), and grade accordingly.

LikeLike

“I can write a super-hard test where you need to be a genius to get 50%, or I can write an easy one where any idiot could get 80%. Or anything in between. I’m supposed to write what sort of test I want, recognize what type I wrote (easier said than done), and grade accordingly.”

– Yes, I understand all this. But isn’t an A always a grade awarded for getting between 90 and 100% (or whatever) in every class? Or can a prof decide that for him an A is anything between 505 and 100% while another prof decides that for her an A is anything between 97% and 100%?

LikeLike

I should add that nobody is all that eager to visit the topic of absolute standards for passing a class. The big political thing right now is graduation rates. A few years ago they talked about “outcomes assessment” which, for all of the flaws in the implementation, at least meant that somebody somewhere was claiming to want to see evidence of learning. Now it’s graduation rates, and nobody wants to hear anything that might get in the way of that. Like, say, firmer standards for passing.

LikeLike

I agree with Thoreau. I’ve had tests where the average is an 80, the test might be scaled so that an 80 might be a B. I’ve also had tests where the average was much lower, and the average was B and a standard deviation above that was an A while a standard deviation below was a C. Next semester I’ll be taking a class where the test averages are known to be in the 30’s and 40’s–in that case, a 40 or 50 could constitute an A or B.

LikeLike

This is like a different planet. 🙂 May I ask why everybody is so hung up on these averages? 🙂

“Next semester I’ll be taking a class where the test averages are known to be in the 30′s and 40′s–in that case, a 40 or 50 could constitute an A or B.”

– I don’t understand this at all. Even groups that take the same sections of the same course in the same year normally show extremely different results. Why would anybody pay attention to what a group scored in previous years?

I’m teaching 2 sections of the same course right now and in the 1st section, the average would be around 85% while in the 2nd section it is around 65%. Of course, all the material, the tests, etc. are exactly the same.

LikeLike

“Even groups that take the same sections of the same course in the same year normally show extremely different results. Why would anybody pay attention to what a group scored in previous years?”

Of course, this also happens. Last year there were two sections of first year physics majors classes each semester, and there was a clear divide in grades. This semester my class is the only section, and a different professor teaches it every semester, so the grades will be different. But next semester, one of the classes is always taught by the same professor, and there’s only one section. I can talk to just about any upperclassman physics major to get an idea of exactly how my numerical grade will lower, and everyone seems to agree that the test averages when they took the class are in the thirties and forties. This is one of the few classes where I can do this, however.

LikeLike

There are a few distinct issues here:

1) Should the percentage required for a given grade be the same in every course of every type? At the places I’ve been at the answer is “no.” One professor can say A = 90% and another A = 80% and nobody cares, as long as the relative difficulties of the tests are reflected in the different grading scales.

2) Should the percentage required for a given grade be the same for the same professor in the same class from one quarter to the next?

if the tests are the same, I would say yes. If, however, I substantially change the tests every term, it’s more complicated.

It’s tempting to say that the tests should be similar, and I aim for that, but here’s the thing: Each midterm covers roughly 4-5 weeks of material. Each week I give them about a dozen homework problems. That means 50-60 homework problems of material for 1 test. Obviously I can’t give them 50-60 problems on the test. I usually give 4-5 problems for the test, depending on the class time and how long the problems are. I try to balance easy and hard problems, but it isn’t always obvious what is really easy. I try to make all but one similar to the homework or class activities, but I have to make small changes, and sometimes those seemingly small changes translate into huge difficulty for the students. I also make one problem deliberately different, to see if they can apply their knowledge in other contexts.

The consequence of this is that a misjudgment on one problem might make 20% of the points far easier than I intended, or far harder than I intended. So I have to pay some attention to the class average.

What I generally do is this: I start with a target grading scale, and then I reserve the right to adjust it if they are getting substantially fewer points BUT the mistakes that I see are intelligent ones, i.e. they are taking reasonable approaches in limited time.

LikeLike

“But isn’t an A always a grade awarded for getting between 90 and 100% (or whatever) in every class? Or can a prof decide that for him an A is anything between 505 and 100% while another prof decides that for her an A is anything between 97% and 100%?”

At all of the institutions I’ve studied or taught at, the faculty have discretion. If the institution said “An A falls in this range” that might be a mandate to write super-hard tests, or a mandate to write easy tests, or something in between, depending on what range they insist on. All of the institutions I’ve studied or taught at have let the instructor decide on the level of the test and set the scoring guide accordingly.

LikeLike

This is very interesting. I never saw anything of the kind anywhere I worked.

How are the GPAs calculated in this case if everybody’s A means something different?

LikeLike

I think it’s the same. An A is a 4.0, an A- is a 3.7, a B+ is a 3.3, a B is a 3.0, and so on.

LikeLike

It’s just how that letter grade is calculated in the first place that’s different.

LikeLike

“How are the GPAs calculated in this case if everybody’s A means something different?”

Literal answer: The scale that Pen outlined

More meaningful answer: We gloss over hard questions.

And besides, let’s say that the school decrees that 90% is the A cut-off in all classes. You still get to decide how lenient or strict you will be in awarding partial credit. You get to decide how nice or tough to be when evaluating that essay. You get to decide whether a person who “mostly” addressed the question gets 90% or less than 90%. You get to decide whether that one omission in their answer is so crucial that they lose 18% of the points (i.e. below an A) or just 8% (still get an A, or at least A-, depending on how the scale is constructed).

Before I tell you whether a given percentage was a good or bad grade, I need to know 2 things: How hard are the questions, and how lenient is the grader with partial credit? You can point to a rubric for the second one, but even then, some rubrics are harsher than others, and they still get applied by human beings with their own biases and perceptions.

LikeLike

Yes, it is all in what 90 means. I currently do 80 A, 60 B, etc., so that I can take off more for errors and so on, and give more difficult questions.

LikeLike

Men are just less competent all around than women. It is so much work working with men, so much doesn’t get done and so many crises happen because nobody thought ahead.

LikeLike

In my university, grades are fixed BUT you can normalize if you think that the fixed grading is detrimental to students.

LikeLike

Lectured-based courses (with a lot of examples, though) are best suited for STEM courses, and class discussions and teamworks are best suited for humanities, languages and literature.

Teaching methods varies accross academic subjects. There’s no “one size fit all” recipe for good teaching.

Grading on a curve is ridiculous. I’ll never do that.

LikeLike

Former engineering and physics student here. Have you ever stopped to think that the majority of STEM students prefer extensive lecturing, aren’t fond of group work and are more self directed learners (often why they are in a math intensive field instead of humanities) and the best lecturers (the men who receive better evaluations) are those who give them what they want.

LikeLike

My friend, I have only been teaching for 22 years. So please don’t try to educate me about the teaching practices unless you have a comparable teaching experience.

As for better evaluations, people who only lecture and do nothing else in class consistently get hugely crappy evaluations. How many evaluations of professors have you had a chance to peruse recently?

LikeLike